Restoring a vintage Tudor Submariner (Part 2)

An ETA 2784 at the heart of the Tudor Submariner

Good watchmakers strive to work clean. That’s easier said than done with vintage, where watches with a lot of mileage often need a little elbow grease (along with ultrasonic waves and foul-smelling chemicals). This well-worn vintage Tudor Submariner is no exception.

The debris in this watch is thick and tar-like. A number of things can cause this. The winding system is made up of steel components sitting directly on nickel-plated brass. Typically a few drops of grease would serve as a protective layer to preserve the plating. f the plating is worn or starts to wear off, the mixture of nickel plating and grease creates a slurry which forms an abrasive compound that only exacerbates the problem. The more the watch is wound, the worse it gets. And as an automatic watch is always winding, old automatic watches with excessively long service intervals are often full of gunk like this.

Inside the automatic barrel

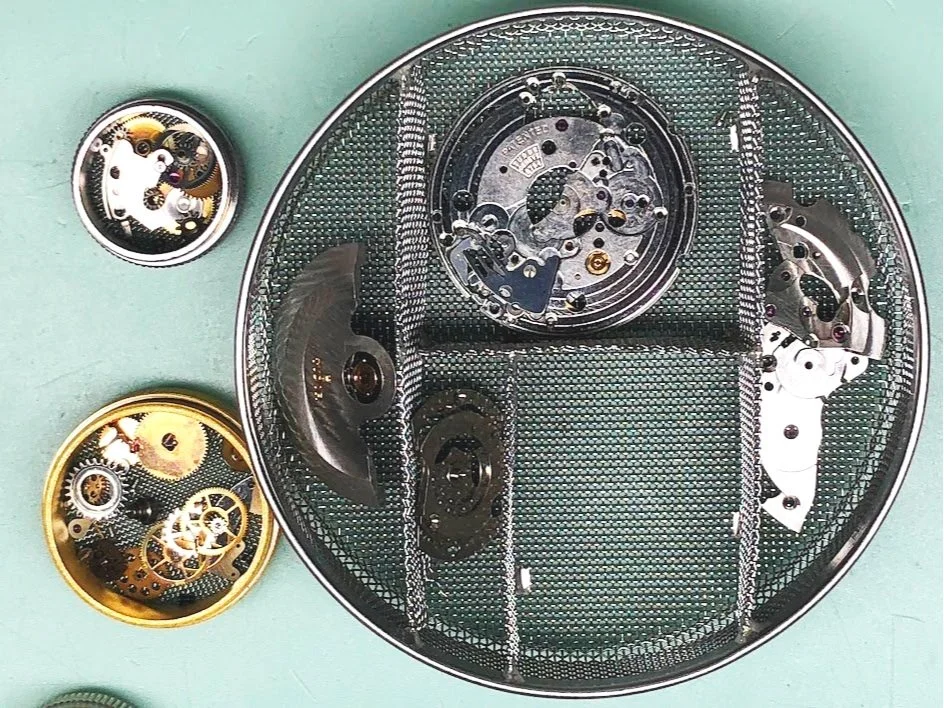

Another contributing factor to debris in a watch is the barrel. An automatic mainspring is not fixed in the barrel, rather it has a bridle that allows it to slip when a certain amount of tension is achieved. Like the winding system, a thick grease is applied to the inside of the barrel wall to prevent wear and to allow the mainspring the slip as necessary. Again, with time and constant motion under high pressure, the brass barrel wall starts to wear. In the photo above you can clearly see the difference in color and texture of the barrel wall. Instead of shiny and silver, it’s dull exposed brass. While some conditions in a barrel can be repaired, this one has reached the end of its useful life. Once replacement parts are sourced and the movement is adjusted, it’s time for final disassembly and one last cleaning.

Ready for the final clean

Servicing a vintage watch, depending on age, quality, and condition, can involve three cleaning cycles. First, the fully assembled movement gets a short bath to wash away the filth. At this point I go through the movement carefully to check condition and end-shakes, make preliminary adjustments, peg the jewels clean, and tear it down completely for a second cleaning. Then a full assembly complete with oiling and regulation. If you’re lucky, this will be the end, but more often than not with really old movements, this is when a lot of fine adjustments, cursing, and troubleshooting take place. That necessitates another disassembly, cleaning, and (hopefully) final reassembly.

Lucky for me, things went pretty smoothly. I’d like to say it was luck, but honestly, I was determined to move this piece off my bench and didn’t take any shortcuts. Thoroughly pegging out jewels, keeping my tweezers and screwdrivers dressed, keeping my bench clean, and leaving nothing to chance were the keys to my success here. This was one of the last pieces I worked on in the jewelry store before leaving, so it was imperative that everything go right. When overhauling a vintage piece, I expect it to run another 5 years without any interventions (a modern watch, about 7-10 years). The last thing I wanted to do was hand over a bunch of half-serviced watches at the end of my time there, or worse, have a comeback.

A little case refinishing to brighten it up, new crown and tube, new crystal, new gaskets, and a new bracelet have really made a big difference in the appearance. I was really happy with the outcome, and so was the owner. Its especially satisfying to restore a watch to brand standards, even when the brand won’t service it anymore.

If you have a watch that you’d like looked at, feel free to fill out a contact form, send along some photos, and I’d be glad to engage in a frank conversation about your goals and the best way forward.